Article by Resonance Academy Faculty: Adam Apollo 2013 – Updated for 2022

For thousands of years, the Aether (ether, æther, aither), a field which connects and permeates all things, was an essential facet of both the philosophy and science of reality in cultures around the world. Also known as “quintessence,” the Aether is the fifth element in the series of classical elements thought to make up our experience of the universe. Greek Stoicheion, Japanese Godai, Tibetan Bön, European Medieval Alchemy, as well as Druidry, Paganism, Wicca, Native American and Tribal Shamanism, and many other spiritual and philosophical lineages all describe the fundamental elements to be:

- Fire

- Air

- Earth

- Water

- Aether

It is worth noting that while the study of these “elements” may seem esoteric, they comprise some of the most foundational areas of scientific inquiry. We simply refer to these studies as: Thermodynamics (fire), Aerodynamics (air), Geophysics (earth), and Hydrodynamics (water). As we will explore further here, the study of Aether is effectively the study of quantum gravity, vacuum fluctuations, and the nature of spacetime itself.

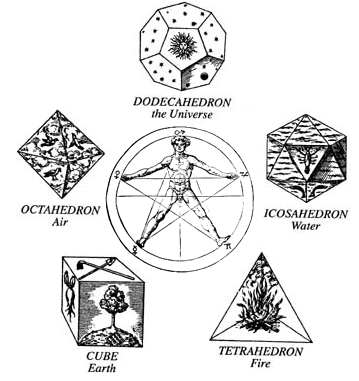

One example representation of the five Classical elements. In this example representation of the classical elements, the dodecahedron represents the Universe, Spirit, or Aether.

Although the Aether goes by as many names as there are cultures that have referenced it, the general meaning always transcends and includes the same four “material” elements.1 It is sometimes more generally translated simply as “Spirit” when referring to an incorporeal living force behind all things.2 In Japanese, it is considered to be the void through which all other elements come into existence. In Hinduism, it is known as Akasha, which simply means “space” in Sanskrit.3

There are also many terms for the movement of energy through the Aether, or the movement of Aether itself. These include qi (also written as chi, ch’i, or ki) which is a traditional Chinese and Taoist concept for the natural energy or “life force” of any living thing. In Hinduism, a similar idea is known as prana, which is the life force which connects all the elements of the universe. For Hawaiian and some polynesian cultures, this field of living force is known as mana. The same concept is known as ruah in Hebrew, as lüng in Tibetan Buddhism, as pneuma in ancient Greece, and vital energy in Western philosophy. It is also popularized by the idea of “The Force” in Star Wars.

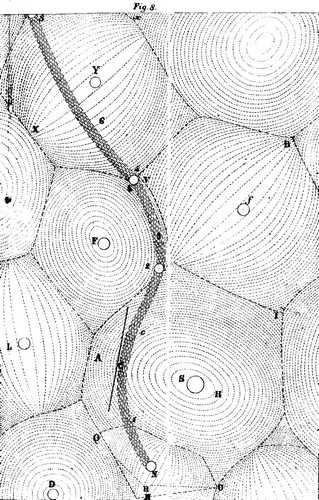

Rene Descartes – Aetherwirbel

CC BY-SA 3.0

The Aether played a central role in our framework of understanding natural phenomena in the universe all the way up until the turn of the 20th century. As we discussed previously, gravity (or the source of mass) was thought by both Rene Descartes and Isaac Newton (as well as Nicolas Fatio de Duillier in 1690, Georges-Louis Le Sage in 1748, and others) to originate from the mechanics of the Aether. During the time of Isaac Newton, this was a somewhat dangerous proposition, as postulation of such “invisible forces working at a distance” was considered to be an introduction of “occult agencies” into science.4

Yet even until the late 1800s, a “luminiferous” (light-bearing) Aether continued to be thought of as the medium through which electromagnetic waves (light) traveled. Proponents of both the particle and wave nature of light agreed that light must travel through some sort of medium.5However, while the theories of the time required the Aether in order to remain consistent, many experiments done to detect this medium failed. Its properties seemed to be too dynamic and ephemeral to test, and many of its qualities had already been explained by alternative theories:

Aethers were invented for the planets to swim in, to constitute electric atmospheres and magnetic effluvia, to convey sensations from one part of our bodies to another, and so on, until all space had been filled three or four times over with aethers…. The only aether which has survived is that which was invented by Huygens to explain the propagation of light.6– James Clerk Maxwell – Encyclopædia Britannica 1878

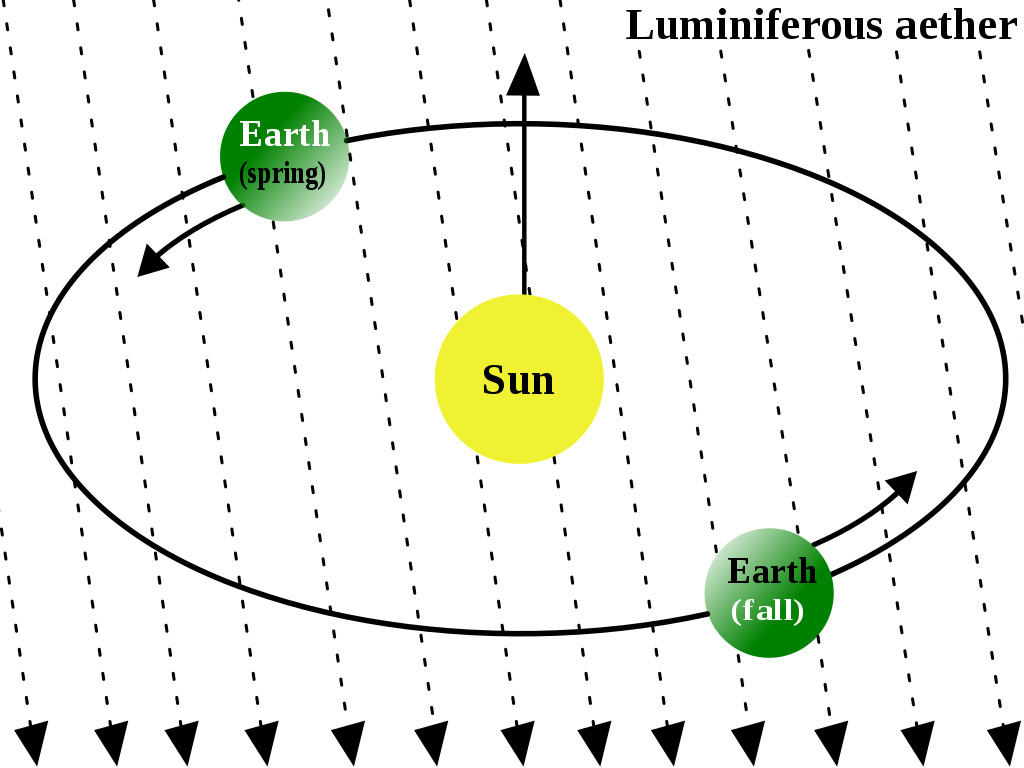

Several theories were produced to reconcile the observed properties of light with the movement of other objects that must be traveling through the Aether, including the Earth. These “Aether drag” theories were developed in consideration of whether the Aether was completely stationary (or moved uniformly) while objects moved through it, or if the Aether was partially “dragged” along with massive objects like the Earth.7 In either case, both theories assumed that movement of the Aether should be detectable from the Earth’s surface, since the Earth both spins and moves around the Sun. Many experiments were concocted to prove (or refute) the existence of the Aether using these simple principles.

One of these experiments done by Hippolyte Fizeau in 1851 measured the speed of light in water, in order to detect if a moving medium or fluid would influence the movement of light traveling through it. Although the effect was much smaller than expected, the experiment showed that a moving medium could in fact adjust the speed of light, supporting the “partial Aether drag theory” of Augustin-Jean Fresnel.8 Although this was disturbing to most physicists at the time, it is important to note that Einstein expressed the importance of this experiment in his work on Special Relativity, over half a century later.9

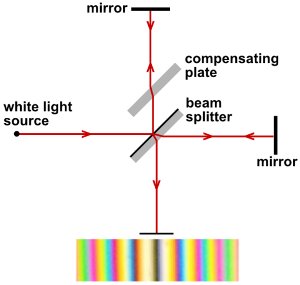

The most famous of these experiments were performed by Albert A. Michelson and Edward W. Morley, and the final test is popularly known as the Michelson-Morley experiment. They set up an extremely sensitive interferometer to measure the “Aetheric wind,” or the presumably detectable movement of the Aether as it passed through a spinning Earth traveling through space. Their experiments were designed to detect a change in the speed of light as low as 0.01%, mostly by viewing subtle changes in the interference patterns of light waves being split and recombined after traveling short distances (using an interferometer). Their results, which showed a negligible change in the light interference, regardless of the time of day or the season, suggested that the Aether must be dragged nearly completely by the Earth:10

AetherWind, Wikipedia – CC BY-SA 3.0

The Experiments on the relative motion of the earth and ether have been completed and the result decidedly negative. … As displacement is proportional to squares of the relative velocities it follows that if the ether does slip past the relative velocity is less than one sixth of the earth’s velocity.-Albert Abraham Michelson, 1887

However, this conflicted with the commonly observed properties of stellar aberration, as an Aether being dragged along by the Earth would be expected to distort our view of the stars in various ways.11 Stellar aberration is an astronomical phenomenon which produces an apparent motion of celestial objects due to the change of the astronomer’s inertial frame of reference. This conflict, and the failure of so many other experiments attempting to verify the “Aetheric wind” resulted in continued rejection of the Aether among the general scientific community.

Michelson-Morley experiment, Stigmatella aurantiaca CC BY-SA 3.0

When Einstein published his Special Theory of Relativity, it solved many of the remaining theoretical problems that required an Aether for explanation by replacing it with a conceptual framework for spacetime itself. He suggested that there was a more simple way of looking at things which did not require a luminiferous Aether; an idea which appealed greatly to the anti-Aether popular science of the early 1900s. The failure of the Michelson-Morley experiment also helped to accelerate the widespread acceptance of Einstein’s proposed constancy for the speed of light.12

Following Einstein’s publishing of General Relativity in 1916, his layman’s book on Special and General Relativity explained:

According to this theory there is no such thing as a “specially favoured” (unique) co-ordinate system to occasion the introduction of the æther-idea, and hence there can be no æther-drift, nor any experiment with which to demonstrate it. … Thus for a co-ordinate system moving with the earth the mirror system of Michelson and Morley is not shortened, but it is shortened for a co-ordinate system which is at rest relatively to the sun.13-Albert Einstein, 1916

This put the final nail in the coffin of the Aether for the scientific community at large. Since that time, the Aether has generally been considered, for all practical purposes, to be non-existent.

Yet shortly after this was published, one of Einstein’s mentors, Hendrik Lorentz, wrote him a letter suggesting that General Relativity reintroduced the Aether, rather than discarding it. While reintroducing the Aether would have doomed any young emerging scientist, Einstein had by this time already earned his fame through Special Relativity and Mass-Energy equivalence (E=mc2). He was still cautious at first, only offering a few public responses that brought up the subject, and his apparent contradictions did not make a “new Aether” appealing to the scientific community.14

Einstein eventually published a complete explanation that would reconcile his apparently contradictory perspectives on the Aether, first by asserting that Special Relativity does not explicitly negate the existence of an Aether, suggesting only that it didn’t explicitly need an Aether to explain the relative properties of electromagnetism and movement. He then clarified and explained the essential importance of the Aether (ether) to General Relativity:

To deny the ether is ultimately to assume that empty space has no physical qualities whatever. The fundamental facts of mechanics do not harmonize with this view. For the mechanical behaviour of a corporeal system hovering freely in empty space depends not only on relative positions (distances) and relative velocities, but also on its state of rotation, which physically may be taken as a characteristic not appertaining to the system in itself. In order to be able to look upon the rotation of the system, at least formally, as something real, Newton objectivises space. Since he classes his absolute space together with real things, for him rotation relative to an absolute space is also something real. Newton might no less well have called his absolute space “Ether”; what is essential is merely that besides observable objects, another thing, which is not perceptible, must be looked upon as real, to enable acceleration or rotation to be looked upon as something real.15

– Albert Einstein, Ether and the Theory of Relativity, 1920

This description, and the rest of his paper published in 1920, suggests that Einstein saw spacetime itself as the “new Aether.” However, this perspective was never popularized and the Aether was slowly forgotten as a “metaphysical” artifact of a previous scientific era.

To clarify Einstein’s meaning further, he is basically suggesting that if an object rotates, there must be a source for that rotation. If the source propelling an object to spin is not the object itself, then it must be the space around the object.

In reviewing this brief history of the Aether, we might inquire as to whether it was appropriate to completely remove it from science and all subsequent science education. Some valuable questions we might ask include:

- Why did so many different cultures and civilizations share a nearly identical concept that is in some cases called an Aether?

- If something is reduced and explained through more specific terms and concepts, is the original inclusive term still valuable? In other words, we know that there are many kinds of Salt, and that the actual scientific composition may be sodium chloride or may be composed of related molecules. Should we remove the term salt, and instead only use molecular names that are more specific?

- Do you think that Einstein’s view of spacetime as a continuous background fabric that connects everything in the universe could be appropriately defined as the Aether?

2022 Updates: The Aether Reborn

In my work since writing this article in 2013, the reasons for Michelson & Morley’s experimental failure has become clear, and the scientific work that further proves a quantum mechanical framework for the structure of spacetime is far more established.

First, in reviewing Michelson & Morley’s experiment, we must address a couple critical assumptions they made:

- The movement of the Earth is unrelated and independent to the movement of the Aether.

- The Aether’s independent state and movement around and/or through the Earth can be detected from the Earth’s surface.

- That the movement of the Aether can be detected moving horizontally or tangential to the Earth’s surface (they used a flat tabletop for the experiment).

The first assumption has gargantuan implications, and appears to be an output of the common methodology of thinking during the 1800’s and early 1900’s. The idea is based on a premise that the Earth is an independent ball, floating around in an “empty space.” Light travels through that space (we see stars and receive sunlight), and similar to the diagram above, the assumption Michelson & Morley made was that Aether must be moving in one general direction through our surrounding “space” and intersecting with the Earth, hitting its surface or passing through it.

However, this does not match either General Relativity or any of the most prominent quantum gravity theories. We know from Einstein that spacetime is curved around centers of mass, and this spacetime curvature bends light. At the very least here, spacetime curvature around Earth would affect any detection of the Aether.

Yet if the quantum gravity theorems of Lee Smolin, Nassim Haramein, myself and others are true, then spacetime itself has a discrete quantum structure and is not “empty” at all. This suggests a view where the Earth is part of an extended “field” of spacetime that is all co-moving, rather than the Earth moving through a surrounding medium. In other words, as Scotty in Star Trek (2009) says:

“Imagine that! It never occurred to me to think of SPACE as the thing that was moving!”

Fluid dynamics reveals this principle quite simply for us every time we pull out the drain-plug in a sink or bathtub. The water moves in a spiral around a central vortex, with sub-vortices throughout, which rotate any little objects in the water. The objects in the water don’t rotate in the water, the water rotates the objects. While this is not an exact model for spacetime (as spacetime is not made of water), this example is easy to visualize and understand.

Essentially, the entire field of spacetime around a Galaxy is co-moving and has significant mass-energy aside from atomic matter (a realization which solves a significant portion of the “Dark Matter” and “Dark Energy” issues and assumptions). In turn, each solar system is a sub-vortex of co-moving spacetime centered around the primary star (or gravitational center between binary or trinary stars in some cases), with further sub-vortices centered around each planetary body with its moons.

The movement of the Aether, gravity, and the movement of mass are all intrinsically interconnected (not-surprisingly), as the movement of Aether IS gravity, and defines the movement of mass.

So assumption #1 is false by these premises. Assumption #2 is partially correct, as we can detect the gravitational flow of Aether downward into the Earth, and in fact light distortion due to gravitational influence from the Earth is well documented.16

However, the Earth is rotating with spacetime’s movement, which is why we don’t feel the “g-force” (gravity) of of traveling ~1000 miles an hour eastward on the surface of the Earth (near the Equator, and relative to an illusionary static point of reference traveling with the Earth around the Sun, but not moving with its rotation). This means it would be impossible to measure the movement of Aether or spacetime on a horizontal instrument apparatus, but not a vertical one, and therefore assumption #3 above is also false.

In simple terms, Michelson & Morley never thought to consider that the Aether is spacetime (as Einstein later proposed), and that spacetime is moving, along with any mass, including the Earth.

The implications for quantum gravity and a unified understanding of the connection between the structure of spacetime and quantum “vacuum” fluctuations are profound, and change the landscape of physics as we know it. Research in this area restores the idea of a foundational field or Aether, but one that is highly defined, classical, geometric, and subtle. It has extremely high energy, but most of that energy is in perfect vibrational tensegrity, a term I coined through my work on quantum geometry. You can learn more about this field, and applications of it in understanding physics as a whole and the generation of matter through my Quantum Geometry course in the Resonance Academy for Unified Physics.

Stay tuned for my forthcoming papers on the origin of the Weak Nuclear Force and its unified physics dynamics, and papers on the quantum geometry of the proton and its relationship to information storage in spacetime.

- Wikipedia – Aether (classical element) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aether_(classical_element)

- Wikipedia – Spirit http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spirit

- Dictionary of World Philosophy by A. Pablo Iannone, Taylor & Francis, 2001, p. 30. ISBN 0-415-17995-5

- Edelglass et al., Matter and Mind, ISBN 0-940262-45-2. p. 54

- Wikipedia – Luminiferous Ether – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luminiferous_ether

- Maxwell, James Clerk (1878), “Ether“, Encyclopædia Britannica Ninth Edition 8: 568–572

- Whittaker, Edmund Taylor (1910), A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity (1. ed.), Dublin: Longman, Green and Co.

- Lahaye, Thierry; Labastie, Pierre; Mathevet, Renaud (2012). “Fizeau’s “aether-drag” experiment in the undergraduate laboratory”. American Journal of Physics 80 (6): 497. arXiv:1201.0501

- Miller, A.I. (1981). Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity. Emergence (1905) and early interpretation (1905–1911). Reading: Addison–Wesley. ISBN 0-201-04679-2

- Shankland, R.S. (1964). “Michelson–Morley experiment”.American Journal of Physics 31 (1): 16–35.Bibcode:1964AmJPh..32…16S.doi:10.1119/1.1970063

- Janssen, Michel & Stachel, John (2010), “The Optics and Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies”, in John Stachel, Going Critical, Springer, ISBN 1-4020-1308-6

- Stachel, John (1982), “Einstein and Michelson: the Context of Discovery and Context of Justification”, Astronomische Nachrichten 303 (1): 47–53, Bibcode:1982AN….303…47S,doi:10.1002/asna.2103030110

- Einstein A. (1916 (translation 1920)), Relativity: The Special and General Theory, New York: H. Holt and Company

- A. Einstein (1918), “Dialog about Objections against the Theory of Relativity“, Naturwissenschaften 6 (48): 697–702,Bibcode:1918NW……6..697E, doi:10.1007/BF01495132 asasf

- Einstein, Albert: “Ether and the Theory of Relativity” (1920), republished in Sidelights on Relativity (Methuen, London, 1922)

- Wikipedia – Pound-Rekba Experiment https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pound-Rebka_experiment